1526 : Westmalle Trappist Dubbel

The heritage of Westmalle Trappist Dubbel dates back to 1856, when a lighter version was brewed as the monk's table beer. Later, in 1926, the recipe was changed up a bit, with the result being Westmalle Trappist Dubbel.

But for a persistent band of monks, there may never have been an abbey at Westmalle, Belgium, and thus, no Westmalle Trappist ale. Which, of course, would have been bad for us. But good for Canada, well...good if they decided to make beer in Canada, but more on that in a bit.

If you have read any of the other Trappist beer histories presented here, or if you remember any of your high school European history, you will recall that the French Revolution was not a particularly good time to be a Catholic in France. It was particularly hard on the larger, more overt, Catholic entities. For an individual person who practiced the Catholic faith, hiding one's devotions from the government was fairly simple - just disavow your faith in public, then continue to practice it in private. And, hopefully not get ratted out. For something as large and as plainly evident as a church, or in our case a monastery, well, this was not so easy. These institutions were the target of a concerted program of elimination by not only France, but also various other European governments.

This photo - courtesy of the Trappist Abbey at Wesmalle - shows the abbey as it is today. One story goes that during World War One, the abbey bell tower was blown up by the major of Westmalle, so that the Germans could not use it as an observation post.

Here is an except of an article written by George J. Marlin called "The French Revolution and The Church (2011):

"Unlike the American Revolution, which was fought to conserve rights and maintain political order, the French Revolution destroyed the fabric of French society. No aspect of human life was untouched. The Committee of Public Safety – influenced by Rousseau – claimed that to convert the oppressed French nation to democracy, 'you must entirely refashion a people whom you wish to make free, destroy its’ prejudices, alter its habits, limit its necessities, root up its vices, purify its desires.'

To achieve this end, the new rational state, whose primary ideological plank was that the sovereignty of 'the people' is unlimited, attempted to eliminate French traditions, norms, and religious beliefs.

The revolutionary governing bodies were particularly determined to destroy every vestige of the Roman Catholic Church because France was hailed by Rome as the Church’s 'eldest daughter' and the [French] monarch had dedicated 'our person, our state, our crown and our subjects' to the Blessed Virgin."

Beginning in February 1790, the revolutionary French government started to pass a number of laws essentially outlawing the Catholic church, including the elimination of all its attendant organizations - including monasteries and abbeys, as well as the confiscation of land, buildings, and other properties. Just being a priest could get one thrown in jail. The Abbey of Notre-Dame de la Grande Trappe, and its monks, did not escape this persecution, with the abbey being closed down and the monks being scattered to the four winds. In April 1791, one group of these drifting La Trappe monks, under the guidance of Dom Augustine de Lestrange, set up residence in an abandoned Carthusian monastery at La Val-Sainte, in Switzerland. While, the "Holy Valley" may have been quite nice, Dom Augustine directed a subset band of French monks to keep moving, this time with the goal of ending their journey in Canada.

For a little more information about the history of the La Trappe Abbey and the Trappists, please jump over to an article called: Trappist Beer - A Primer in 688 (+/-) Words. Click here, and then scroll down a ways.

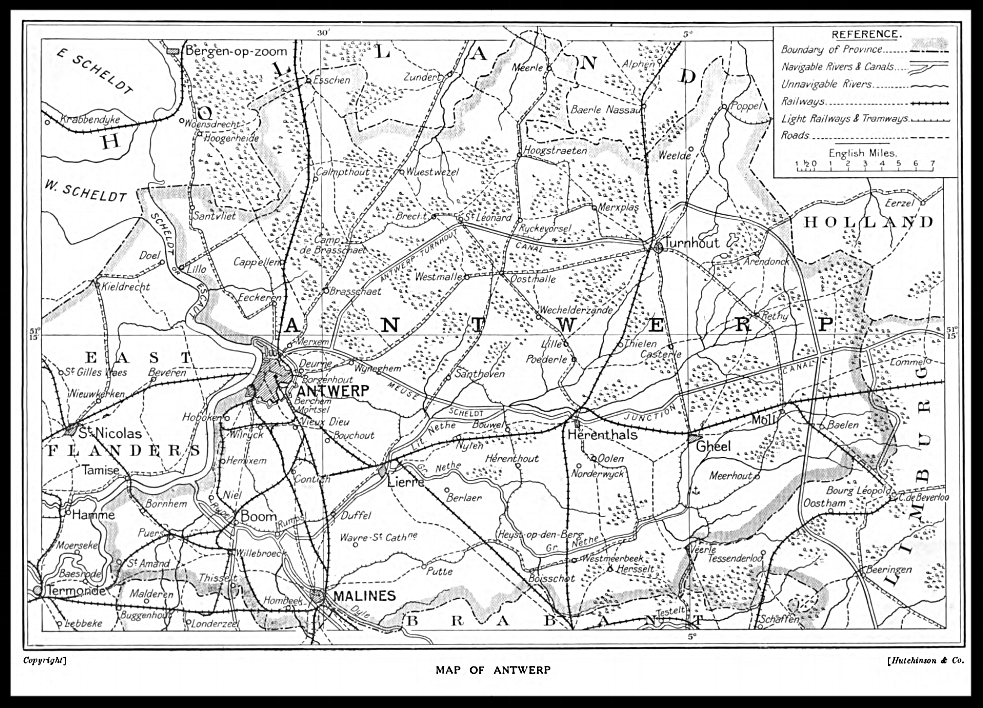

The road that comes of from the lower left hand corner of this map, is the road that runs from Antwerp to the town of Turnhout. As can be seen, it runs through the village of Westmalle and Oostmalle. Look just to the southwest of Westmalle - the Trappist Abby at Westmalle. Image from a 1945 U.S. Army map of Belgium.

Please pardon me while I go off on a short tangent: Back in January 1782, the Austrian ruler Joseph II (House of Habsburg-Lorraine) made his Secularization Decree, which degreed that many religious houses, namely Catholic houses, must be shuttered. At the time, his domains included what was then known as the Austrian Netherlands, which included much of the area of Flanders - northern Belgium of today. His decree included the Cistercians, and was rather odd because at the time he was considered the Holy Roman Emperor. Of course, just because one is the Holy Roman Emperor does not mean one gets along with the Pope, and Joseph II was really trying to curb the power of the Catholic Church. Joseph - also known as the "Enlightened Despot" - was actually quite tolerant of other religions, and his Edict of Toleration allowed Jews, Protestants and the Greek Orthodox to openly practice their faiths. Of course, none of these groups were anywhere near as powerful as the Catholic Church. Anyway, Joseph II lost the Austrian Netherlands in 1790, and a couple of weeks later he was dead.

So, around this time there were a number of folks, mostly sympathetic nobles living in and around the city of Antwerp, who at the behest of the Bishop of Antwerp Monseigneur Nelis, tried to purchase an old, disused priory - the Priory of Corsendonk - just a few kilometers northeast of Antwerp. The idea was to establish a monastery there, perhaps for some of the wandering Trappist monks from the monastery at La Val-Sainte. Bishop Nelis had lived through the times of Joseph II, and had seen first hand the dissolution of dozens of monasteries. Unfortunately, the purchased failed, partially due to the fact that although Joseph II was dead and gone, many of his edicts remained in place. Another attempt to secure land was more successful, when on 3 June 1794, an old estate called Nooit Rust - Never Rest or Restless - was purchased. Rather bizarrely, just as the purchase was being finalized, Dutch government officials rousted the Bishop and many of his followers, who had to go into hiding, and although the sale went through, Nooit Rust was left unoccupied.

You really can't get much more peaceful than this. Another image courtesy of the Trappist Abbey at Westmalle, showing the abbey wall surrounding the brewery.

Anyway, back to our story. Earlier, on 28 August 1793, the aforementioned band of monks - 10 in all - left the La Trappe monastery at Val-Sainte, Switzerland with the intention of finding a ship to take them to Canada, the goal to establish a monastery in North America. Led by Jean-Marie De Bruyne, the band essentially walked to the port city of Amsterdam, but once there they were unable to secure passage on a ship. Re-enter Bishop Nelis, now out of hiding, who invited the stranded monks to come to Nooit Rust, and set up a religious enclave there, rather than going all the way to Canada. It took a few months, but in May 1794, the band of French monks arrived in the area of the small village of Westmalle - sometimes written as West Malle - and on 6 June, had taken up residence at their new home at Nooit Rust. Today, the date 6 June 1794, is celebrated as the founding of the Abbey of Our Lady of the Sacred Heart - Abdij van Onze-Lieve-Vrouw van het Heilig Hart - or more familiarly called the Trappist Abbey at Westmalle. So far, so good - right?

So, here come the French, marching thorough this portion of what would later become Belgium, chasing off all the monks in their path. So, not two weeks after they took up residence at Nooit Rust, the Trappist monks were on the run again. On 17 June 1794, the monks fled Nooit Rust and headed out in the general direction of Germany. First they stopped at the Benedictine Abbey of Brauweiler, then settling in as guests at the Cistercian monastery at Marienfeld, while later in 1796, helping to establish a Trappist monastery at Darfled. Still, Nooit Rust was their home, which combined with overcrowding almost everywhere they went, convinced several of the monks to return to Westmalle. By 1802, life had calmed down a bit, some tolerance by the French was forthcoming, and the monks actually had the opportunity to improve and expand the rather dilapidated Nooit Rust.

Then, here come the French, again. On 28 July 1811, Napoleon issued a degree, which among many other things, closed down all Trappist institutions in his domain. The monks were on the road again, and except for a couple of caretaker monks dressed in secular, non-Trappist garb. The buildings at Nooit Rust were used as a military barracks. But, Napoleon was ousted in 1814, the foreign soldiers all left, and the Trappist monks returned to Nooit Rust. So, everything is good now - right.

Well, maybe. With the departure of the French, the governmental void was filled with the Dutch, again, and the Dutch King William I was not the greatest of fans when it came to many religious institutions like the Trappists. However, on 25 January 1822, William I did issue a royal decree authorizing the monastery at Westmalle, with some stipulations. Mainly, the monastery could not be a purely contemplative order, rather William mandated it provide real benefit to the local area, requiring the monks to set up a farming operation, as well as a school and a small hospital. In 1830, out go the Dutch and Belgium became a country. For much of its existence, the church hierarchy considered the monastery at Westmalle to be simply a priory, however on 22 April 1836, it was given full status as an abbey. And, on 31 October 1842, the abbey was given full royal recognition by the Belgian government. Wow, European history can be complicated.

***

Back in the late 19th Century, the town of Westmalle was one of those small Belgian country villages that the tourist guidebooks rarely mentioned. If a book did mention Westmalle it was usually just noted as a quick checkpoint to ensure the traveler was on the correct road from Antwerp to Turnhout. One would hope, however, that the tourist of the late 1800s, as he or she pedaled away on the road to Turnhout, would notice a thriving abbey in the countryside just west of the village of Westmalle. As per custom, the Trappist Abbey at Westmalle has been required to be self sufficient in all aspects of life, as well as tending to the local community. For years the monks worked a large farm, raised dairy cows and ran a diary operation, although since around 1932, the land is mainly used to raise the dairy cows. So, what about the beer?

An itinerary from the 1901 Continental Cyclist Touring Guide showing the village of Westmalle as simply a checkpoint between Antwerp and Turnhout. Not much to see here folks. At least Turnhout has a chateau. I wonder if back in 1901, a thirsty cyclist could get a refreshing ale from the abbey.

Not so fortunate for the first band of monks to take up residence at Nooit Rust, the strict rules of Dom Augustine de Lestrange allowed the monks to drink only water. However, Dom Augustine died in 1823, and by 1836, with the reevaluation and realignment of various tenets of Trappist life, beer was now allowed. And, a bit of wine if you were sick. History does show, however, that previous to this the monks did drink at least a little beer, despite de Lestrange's prohibition. Whether they made it themselves is not recorded.

On 1 August 1836, Dom Martinus, who had just been appointed as abbot, initiated construction on a new brewery, keeping with the tenet that all production must be kept within the monastery's walls. On 10 December 1836, the monks enjoyed their own beer for the first time. By 1856, the brewery was making two beers, a low alcohol pale beer for the monks, and a higher strength dark beer for outside sales. According to extent abbey records, the first outside sale of Westmalle beer was on 1 June 1861, although evidence, as noted above, suggests sales began before that date.

Of course it goes without saying that World War One had a negative impact on the abbey, and all its functions, with most of the monks fleeing to the Trappist monastery at Zundert, in the Netherlands. (Hmmm...Zundert, that does sound familiar.) And, of course, when the German army came through they used the monastery buildings for barracks and stables, and stole all the strategic copper from the brewery. It was not until 15 February 1922, that the brewery resumed operation. Interestingly, in 1933, one of the monks - by the name of Prior Ooms - registered the name "Trappist Beer" for the abbey. At the time, the abbey was planning a major expansion of their brewery, seeing the sale of their beer as a prime - and stable - source of income for both maintaining their abbey and for outside charitable work.

Although for almost three decades now the brewing of Westmalle Trappist Ales has been done by laymen, the monks at the Trappist Abbey at Westmalle still supervise the overall process to ensure it remains a true Trappist ale. This photo - showing a portion of the brewery today - is courtesy of the Trappist Abbey at Westmalle.

World War Two, while it caused a down turn in production at the abbey, mainly left the abbey intact, and the monks on site. By the 1990s, the brewery had grown to the point that its operation was a bit much for the monks, and was starting to interfere with the basic calling of a monk. Thus in 1998, the brewery was removed from the nonprofit abbey organization, and turned into an independent commercial business. Whereas the brewery used to be run by many monks and only a few laymen, today it is run by many laymen, but still under the strict supervision of a few monks. As noted in Jef Van Den Steen's book "Trappist - The Seven Amgnificent Beers" (2010), then Abbot Ivo Dujardin said, "In this new phase, I feel it is of primordial importance to safeguard the monastic cachet of our brewery and it special economy, in order that the 'authentic Trappist Product' label remains genuine and does not become empty or false."

Today, the Trappist Abbey at Westmalle brews three primary beers - a dubble, a triple and what is called an "extra," this last beer being a lighter beer made for the monks.

So much for going to Canada.

The road from Antwerp through Westamlle then Oostmalle and on to Turnhout. A map from the book "Belgium - The Glorious," - 1915.